One challenge in improving quality of life for patients and loved ones affected by KIF1A Associated Neurological Disorder (KAND) is that there are not always clear-cut answers for symptom management. While we don’t have all the answers, we’ve gathered some resources on vision in KAND that you can discuss with your doctor.

Unfortunately, vision conditions are one of the most common symptoms of KAND, affecting 84% of patients. Severity and progression vary widely between patients, but the most recent Natural History Study recommends “… regular assessments with a neuro-ophthalmologist to assess for optic nerve atrophy and cataracts that we have observed in some older individuals.”1. But what does vision loss look like, and how do we surveil it?

A note: Throughout this page we will be referencing the most recently published data from the Natural History Study, where you can find more in-depth information on this and other symptoms.

Identifying vision loss

Vision is one of the primary ways we interface with the world around us; it’s also a highly personal perception. Many with glasses remember the childhood discovery that others saw the world differently, often through a conversational fluke when someone points out a detail. “Since individuals with KAND may be cognitively impaired, it may be difficult for them to describe their visual symptoms, especially if they have never had normal vision.”1

People who struggle to verbalize their experience may have their behavior misinterpreted:

- Someone who can’t read the chalkboard from their seat may be inattentive or disruptive

- A child who can’t distinguish faces at a distance may not seem emotionally responsive

- A baby struggling with vision loss that compromises their balance may seem disinterested in their environment.

In fact, the KAND Natural History Study found significant differences between caregiver-reported visual symptoms, and those identified by in-person assessments, highlighting the need for thorough assessments in new patients when possible:

| Ophthalmic characteristic | Caregiver report | In-person assessment |

| Color vision deficits | 0/12 | 11/12 |

| Visual field defect | 0/12 | 11/12 |

| Depth perception defects | 1/10 | 10/10 |

| Optic nerve atrophy | 10/22 | 20/22 |

We are still learning about vision loss in KAND through the KOALA study, and there are currently no KAND-specific vision treatments, but the following symptoms have been identified:

- Visual Acuity: What we typically think of as sharpness of vision, this is the ability to make out details at a distance. Loss of visual acuity is commonly addressed with glasses, but this may have more complex causes. The latest KOALA results found that the acuity is 20/43 in children, and 20/116 in adults.

- Field of vision (peripheral vision) impairment: This is “side vision” or how much of our peripheral surroundings we can see when looking in one direction. It may manifest as blind spots or fuzzier peripheral vision.

- Color vision impairment: This symptom may be particularly hard to diagnose in patients who struggle with language, and can have a pervasive impact on quality of life if unrecognized.

- Depth Perception: Our two eyes see the world from slightly different angles; our brains compare these images to determine the distance of objects. When our eyes can’t coordinate to focus on the same object due to misalignment of the eyes, this is called strabismus. Strabismus is common in individuals with KAND, and it can compromise depth perception or cause double vision.

- Movement compensation: Our eyes constantly make adjustments so the world doesn’t become a dizzying, bouncing mess every time we move. At the end of this sentence, turn your head to the left while maintaining your gaze on the period. The muscles of your eyes automatically moved your gaze to the right; this is called an oculomotor (eye movement) reflex. Nystagmus is a term for when this reflex doesn’t work, and it can cause severe vertigo and dizziness during movement, even the small subtle movements that happen when you sit in place.

Visiting your Ophthalmologist: KIF1A-Associated Neurological Disorder (KAND) Ophthalmic Exam List from Dr. Aliaa Abdelhakim

Wondering what to look for when you meet with your ophthalmologist? We’ve compiled a printable cheat sheet of potential visual symptoms in KAND, signs to look out for, and relevant tests, with guidance from Dr. Aliaa Abdelhakim, MD, lead ophthalmologist in the KOALA clinical endpoint study.

Because KAND is a neurodegenerative disorder, it can be helpful to follow with a neuro-ophthalmologist who specializes in neurological contributions to visual deficits and can test visual processing in the brain. If KAND patients have reduced vision, a referral to a Low Vision Specialist should be considered to address visual disability using directed functional adjustments and low vision technologies.

A deeper look: how could KIF1A dysfunction impair vision?

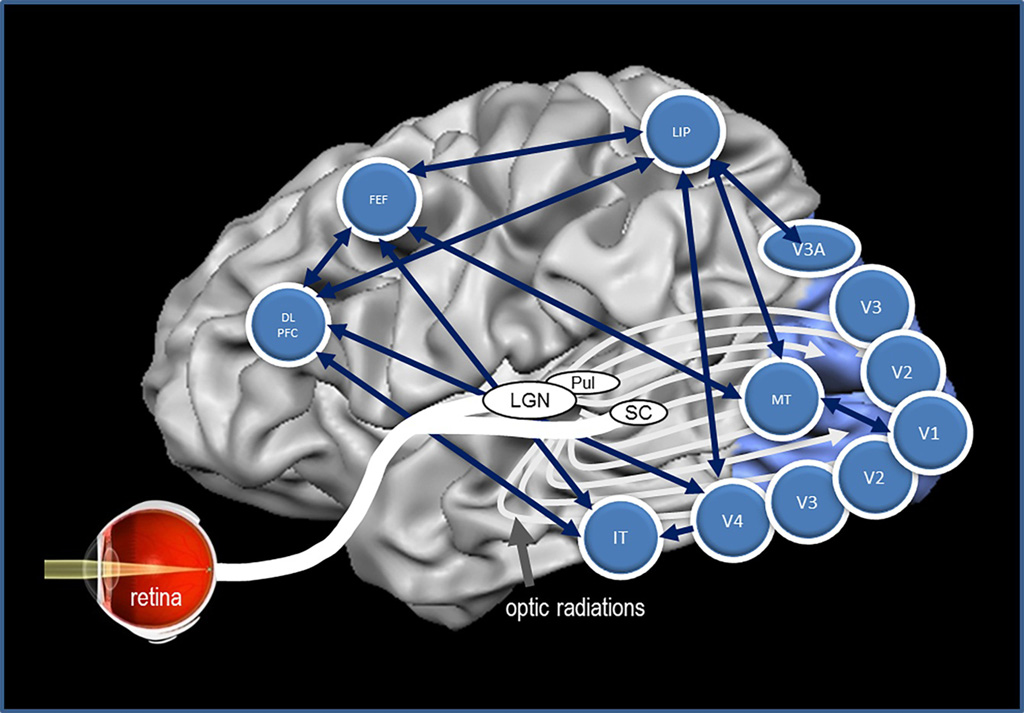

When we look at our surroundings, we don’t send a fully formed image from our eyes to our brain; light is received by 96 million photoreceptors in each eye, whose activity operates 1.5 millions neurons, which filter and route information from the eye to the brain. Through multiple stages of processing, simple bars and colors are combined into the rich variety of sights we can see, and then relayed to other brain regions that plan appropriate movements or associate meaning to visual stimuli:

As you can see, visual information has a lot of long axonal roads to travel, and it’s important that signals arrive to their destination in a timely and coordinated fashion. If KIF1A dysfunction interrupts cargo transport and these circuits are damaged, it could cause diverse visual perception symptoms: Here are some examples of visual circuits that could be impacted in KAND.

- Optic Nerve Atrophy: The optic nerve travels from the eye to the brain, and is a bottleneck for visual information; improper development or degeneration can have profound effects on basic visual processing. Optic nerve thinning doesn’t always have a 1:1 relationship with vision. Some patients with noticeable atrophy still have relatively good vision, and some patients experience symptoms before noticeable atrophy. For this reason, sensitive measures of optic nerve thickness are recommended to track changes over time.

- Cerebral/Cortical Visual Impairment: This is impairment at the level of the visual cortex, which is the part of the brain that synthesizes visual inputs coming from external sources. This is a common feature in KAND, and may be under-identified due to the testing required. Dysfunction in the visual cortex can directly affect vision, but can also impact how we recognize, interpret, and react to visual stimuli. A combination of behavioral and electrophysiological testing can determine types of cerebral visual impairment.

- Impaired Eye Movement: Our eyes are constantly moving, both by our direction and automatically to help us interpret and navigate our environment. Patients with KAND already struggle with motor symptoms, and compromised depth perception (strabismus) and balance (nystagmus) can worsen these problems.

There’s still a lot we don’t know about KIF1A’s relationship with vision, or the specific circuits that are vulnerable in KAND; Research Network members recently began investigating visual pathology in our animal and cell models so we can get a better understanding on which circuits are affected, and why.

Therapeutic opportunities and leads in vision

For a disease community as heterogeneous as KAND, it’s important to consider how different symptoms can be researched and therapeutically approached. There are many advantages to investigating vision loss in KAND:

- High potential impact on multiple facets of quality of life.

- Vision isn’t all-or-nothing, incremental improvements can make a big difference!

- The optic nerve is an accessible CNS (central nervous system) target for less invasive administration methods, and may present a viable alternative for patients who aren’t eligible for other methods of CNS treatment.

- Vision is a well-studied system for treatment/prevention of secondary neurodegeneration, and several therapeutic targets being studied are known KIF1A cargo.